Wireless Community Networks In Action

Wireless community networks (WCNs) provide a viable alternative to corporate or municipal wireless networks. They grow through collective action focused on installing wireless hardware in households and on rooftops to recieve and broadcast Internet signal. In a WCN, everyone on the network is a contributor rather than simply a consumer.

While a network where everyone is a contributor may sound radical or even far-fetched, there are many projects under active development in the United States that exemplify its feasibility. Most of these projects are mesh networks, which are just one kind of network capable of achieving the goal of community ownership. Mesh networks are particularly optimal for this purpose, though, because they are dynamic – routers can be disconnected at random without the network breaking down. For those interested in the nitty-gritty technical details of meshing protocols, see the Yggdrasil, CJDNS, BMX, B.A.T.M.A.N., and/or babeld projects.

All of the projects I’ve presented below focus on closing the digital divide, but some have taken a more active approach to this goal. In particular, DCTP and Red Hook have stood out in this regard. NYC Mesh has probably the most efficient operational setup, and is a model for rapid expansion. Ultimately, each has its own strengths, weaknesses, actors, neighborhoods, needs, and level of maturity. This diversity of networks is one of the strengths of the WCN model, but a good synopsis of existing projects is rare online. If you would like to see your network represented on this list, or have any additions/corrections, please contact the author!

Detroit Community Technology Project

Formed: 2015

Location: Detroit, MI

Network Size (2019): 200+ Households

Funding: Sliding-scale subscriptions; Donations

Technology: Commotion

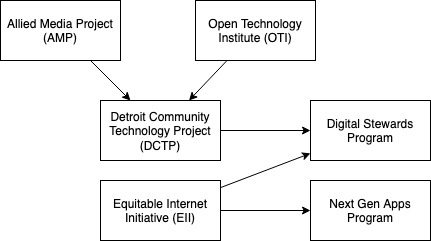

Frustrated by exceptionally bad access to the Internet in Detroit (with 70% of residents not served at all by commercial ISPs,) the Allied Media Project (AMP) partnered with the Open Technology Institute (OTI) in 2014 to form the Detroit Community Technology Project (DCTP.) This project was initiated in order to train digital stewards in the skills necessary to build their own network infrastructure. The Equitable Internet Initiative (EII) was formed in 2015 to assist the Digital Stewards in this process.

The network runs on Commotion firmware. Most hardware is low-cost omni-directional APs, but there is also a relay layer composed of directional antennas. All of the network infrastructure was installed by the Digital Stewards, but the EII played a critical role in coordinating the installs. It is not clear who owns what network hardware, who paid for it, or how it is upgraded. (14-APR-2019)

Complementing the previously mentioned organizations, the Next Gen Apps program educates middle school and high school students about web development so that they can contribute apps to the network. So far, this program has graduated students that have created apps to monitor local air pollution levels, highlight black owned businesses, and more.

Overall, the Detroit community wireless project and all its actors have a strong commitment to digital justice principles. Inclusion has been a central theme in their project. They’ve published ‘zines, created documentation, and generally advocated for this approach consistently. Their Digital Justice Principles are worth checking out for more information about what a commitment to digital justice means in practice.

NYC Mesh

Formed: 2013

Location: New York City, NY

Network Size (2019): ~300 nodes

Funding: Low cost subscriptions; Donations

Technology: Batman-adv

Our neighbors in NYC have been hard at work since 2014 installing Batman-advance routers on rooftops in order to bypass the “cable cartel” in their city. They have been able to provide speeds up to a gigabit, and most network users voluntarily pay $20 per month for access.

NYC Mesh is a 501(c)3 non-profit, and relies on volunteers for their installs. They’ve partnered with Silicon Harlem, which has its own community wireless project planned for 2019. NYC Mesh’s own expansion plans are very ambitious, averaging 3.5 installs per week this March.

While the organization does approach digital justice issues, there is comparatively less emphasis than what’s happening in Detroit and Red Hook. The website does point us to a handy volunteers page, and training materials, though. This judgement is based on a preliminary review of their online resources, and could of course be different on the ground.

Their network has seen very rapid expansion, possibly as a result of their willingness to “act like a business” when it comes to handling support, installs, etc. Probably the greatest achievement of NYC Mesh is their operationalization of volunteer efforts. They have an online ticketing system for customer service requests, and a clear onboarding process for new node operators and volunteers.

Red Hook Wifi

Red Hook is a unique community in Brooklyn that is cut off from the rest of the city by a highway. There is little to no public transportation into the neighborhood. Their network grew in a very tight-knit community, and provides a lot of opportunities to local youth interested in working with technology.

They have partnered strongly with local businesses, and boast a paid fellowship program for ages 19-24 to learn about working in the technology industry. RISE NYC covers the physical costs of their network, while the Red Hook Initiative pays for all the labor. Their network runs Commotion, and was the only way to connect to the internet during the fallout following Hurricane Sandy in 2012.

Another unique aspect of their network the emphasis on resilient installations (i.e. nodes powered by solar panels.) This approach has been replicated elsewhere, but never called out specifically on other projects’ websites.

People’s Open Network

The People’s Open Network is based in Oakland, and is partnered with Sudo Mesh for their software. This is unique from the projects listed above, because those projects do not necessarily have an ongoing relationship with their software development teams.

The routers on the People’s Open Network run a custom firmware, called sudo-wrt, which uses babeld for its underlying routing protocol.

There are useful applications being built by Sudo Room hackers on this network. Garden Mesh is a highly specialized kind of mesh network that was developed by Sudo Mesh and Counter Culture Labs during a conference at Omni Commons in 2017. It gathers sensor data from plants, which are meshed together using micro-computers. disaster.radio is a disaster-resilient communications network powered by the sun. The People’s Open Network also hosts many events in their area.

This project is supported by Sudo Mesh, Sudo Room, Omni Commons, and the Internet Archive. These organizations provide software, meeting space, and free bandwidth.

Pitt Mesh

This project is based in Pittsburg, and was started by Meta Mesh in 2013. They operate piNet, a network of failure-resistant rasperry pis that host local services like a community hub. Their network consists of about 65 nodes.

Personal Telco Project

Formed: 2000

Location: Portland, OR

Network Size (2019): ~82 access points

Funding: Donations

Technology: Not actually a mesh-net

This project consists of almost 100 hot-spots throughout the city of Portland, Oregon. The group was established in 2000, and is not a mesh network. (As far as I can tell…) This is more of a hot-spot sharing initiative, but since it appears to provide strong internet access, I’ve included it here.

Conclusion

As you can see, there are many active wireless community-owned networks in the United States. These all have different organizational structures, diverse affiliations, and differing goals. There really is no one correct way to build a WCN, but there are some clear patterns among the most active. One is a focus on digital justice. Another is the involvement of a 501(c)3 capable of accepting donations. A third component, and perhaps the most important, is a dedicated team of resident installers/maintainers of the network. These three components are what Mass Mesh will seek to cultivate in the coming year. Check back for updates!